|

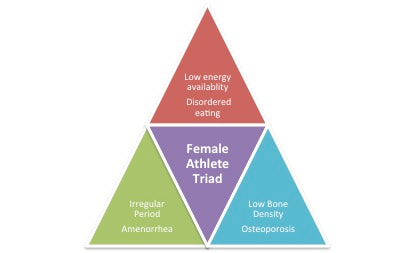

The Female Athlete Triad is a condition that includes three components:

– Low bone density (risk for stress fractures and osteoporosis) – Disordered eating – Amenorrhea (no menstrual cycle for three months or more) (Matzkin et al., 2015). The consequences of the Female Athlete Triad can be long-term and irreversible, and include stunting of growth, reproductive dysfunction, and osteoporosis. Any female athlete is at risk for this syndrome, but women who participate in dance are more susceptible because of the desired lean aesthetic and rigorous training schedule (Barrack et al., 2014). Peak bone density is achieved between ages 18 to 25 years. Poor nutrition (i.e., insufficient calories, calcium and vitamin D), stress, and intense training lead to hormonal disruption during the peak-forming period. Reduced estrogen production leads to bone resorption, and this can occur despite the fact that load-bearing physical activity such as dance usually improves bone-mineral density. Some female athletes have bone density similar to older postmenopausal women, which is dangerously low. One study reported that 80% of female dancers diagnosed with stress fractures of the second metatarsal started their menstrual period late (O’Malley, 1996). This type of bony injury requires at least 6-8 weeks to heal and even longer to rehab. The remedy for Female Athlete Triad requires that energy needs be met consistently, either by modifying diet or reducing exercise. If body fat is inadequate, restoring body weight to a healthy level is the best strategy for normalizing menstrual periods and improving bone health. References:

1 Comment

3/1/2019 13 Comments Stress Fractures in Dancers Stress fractures occur in up to 46% of dancers during their career (Delegete, A). Over 60% of these fractures occur during puberty. Decreased strength, proprioception, and balance control, as well as poor technique can lead to increased stress to the bones and thus increased risk for stress fracture. Females are twice as likely than males to have a stress fracture secondary to caloric restriction, reduced bone mineral density, and menstrual irregularities (Delegete, A). RISK FACTORS

POSSIBLE SIGNS/SYMPTOMS:

REDUCING RISK Rehabbing a stress fracture can involve complete rest for 6 to 10 weeks. It is important to recognize possible signs and risk factors to avoid bone damage.

References: 1) Delegete, A. Health Considerations for the Adolescent Dancer. A webinar through the Harkness Center for Dance Injuries. Accessed September 23, 2018. 2)Weiss, David S. Stress Fractures in Dancers: Evaluation and Treatment. A webinar through the Harkness Center for Dance Injuries. Accessed November 11, 2018. 11/4/2018 3 Comments Eating for Immunity The immune system provides protection from seasonal illness such as the common cold as well as other health problems including arthritis, allergies, abnormal cell development and cancers. Dancers are exposed to physical stress from training, which increases susceptibility to illness. Additionally, working in close proximity with other dancers increases exposure to infection. Nutrition plays an important role in maintaining immune function to protect against infection. Learn how to boost your immunity by including these nutrients in your eating plan. Proteins form many immune cells and transporters. Try to consume a variety of protein foods including seafood, lean meat, poultry, eggs, beans and peas, soy products and unsalted nuts and seeds. Vitamin A helps regulate immune function and protects from infections by maintaining healthy tissues in skin, mouth, stomach, intestines and respiratory system. Vitamin A is found in foods such as sweet potatoes, carrots, kale, spinach, red bell peppers, apricots, eggs or foods labeled "vitamin A fortified," such as cereal or dairy foods. Vitamin E works as an antioxidant to neutralize free radicals. Include vitamin E in your diet with fortified cereals, sunflower seeds, almonds, vegetable oils (such as sunflower or safflower oil), hazelnuts and peanut butter. Vitamin C protects stimulates the formation of antibodies, which are necessary to fight infection. Citrus fruits such as oranges, grapefruit and tangerines, red bell pepper, papaya, strawberries, and tomato juice are good sources of vitamin C. Zinc is critical for wound healing and aids the immune system. This mineral can be found in lean meat, poultry, seafood, milk, whole grain products, beans, seeds and nuts. Other nutrients, including vitamin B6, folate, selenium, iron, as well as prebiotics and probiotics, may also influence immune response. References: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (2017). Protect Your Health with Immune-Boosting Nutrition. Retrieved at eatright.org. 10/3/2018 1 Comment Pre- and Probiotics and HealthProbiotics are beneficial bacteria that exist in our gastrointestinal tract. Prebiotics feed the beneficial bacterial colonies and work synergistically with probiotics. In other words, prebiotics nourish and maintain probiotics, which restores and improves gut health. Probiotic sources include yogurt, kimchi, sauerkraut, miso, tempeh and cultured non-dairy yogurts. Some good sources of prebiotics are bananas, onions, garlic, leeks, asparagus, artichokes, soybeans and whole-wheat foods. Products that combine both are called synbiotics. For best results, try combining pre- and probiotics in your usual diet by enjoying bananas with yogurt or stir-frying asparagus with tempeh.

Are probiotic supplements necessary for everyone? Probably not. In fact, there are risks associated with use of probiotic supplements. These include: systemic infections, metabolic disruption, excessive immune stimulation in compromised individuals, gene transfer, and gastrointestinal side effects (Doron & Syndman, 2015). By consuming regular food sources of probiotics, you can safely maintain the integrity of your gut and avoid disrupting your body's natural microbiome. At a minimum, prebiotics and probiotics are keys for optimal gut health. Research indicates that the gut bacterial environment has implications beyond digestive health. The microbiome may impact weight management and risk of central nervous system diseases (Shreiner et al., 2015). Incorporating health-promoting functional foods, such as foods containing prebiotics and probiotics contributes to a healthier you! Our registered dietitian, Nasira, can provide more advice on obtaining pre- and probiotics for your specific health needs, especially if you have gut issues or a weakened immune system, Contact her today: (425) 445-3914 or nasirasnutrition@gmail.com. References: Doron, S., & Snydman, D. R. (2015). Risk and safety of probiotics. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 60(suppl_2), S129-S134. Shreiner, A. B., Kao, J. Y., & Young, V. B. (2015). The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Current opinion in gastroenterology, 31(1), 69. 9/10/2018 1 Comment Am I ready for pointe work?A dancer’s progression to pointe work is a much anticipated moment. It is completely normal to be excited about this milestone, but it is extremely important not to rush into pointe work. There are a variety of factors that need to be considered to ensure that a dancer is ready to sufficiently meet the demands of pointe work.

Criteria for pointe readiness based on expert recommendation:

What are the risks if I start too early? If the dancer begins pointe work without adequate range of motion and/or neuromuscular control, they can hinder proper technique development, foster bad habits, and potentially increase the amount of stress on the developing bones as well as the surrounding musculature. There is rapid bone growth and remodeling between the ages of 9-15 years old. During this time, growth plates are weaker than the surrounding bone, making them less resistant to different forces and more susceptible to injury. In addition, there are neuromuscular changes that occur as the dancer accommodates to rapid growth. The dancer takes time to adapt to changes in strength, flexibility, and proprioception, which ultimately influences motor control and performance en pointe. Therefore, chronological age cannot be a sole marker for pointe readiness (Richardson 2017, Shah 2009). It is important to communicate with your ballet teacher regarding the progress of your technique and whether you meet the criteria to initiate pointe work. Health care professionals (MD, PTs) with a background in dance can assist in conducting pointe readiness screens. *Description of pointe readiness tests:

1) Richardson, M. Principles of Dance Medicine, Functional Tests to Assess Pointe Readiness. A webinar through the Harkness Center for Dance Injuries. Accessed Feb 23, 2017. 2)Bullock-Saxton, J. E., Janda, V., & Bullock, M. I. (1994). The influence of ankle sprain injury on muscle activation during hip extension. International journal of sports medicine, 15(06), 330-334. 3) Richardson, M., Liederbach, M., & Sandow, E. (2010). Functional criteria for assessing pointe-readiness. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 14(3), 82-88. 4) Shah, S. (2009). Determining a young dancer's readiness for dancing on pointe. Current sports medicine reports, 8(6), 295-299.  According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, nutrient dense foods are those that provide an average of 10% or more daily value per 100 calories of 17 nutrients, including potassium, protein, fiber, iron and calcium (DiNoia, 2014). While there are several fruits and vegetables that are nutrient dense, there are some in particular that are best in the summertime, because they also happen to be refreshing and help with hydration. Citrus fruits and berries are excellent choices for summer snacking. According to CDC’s nutrient density approach, the healthiest of them all is the strawberry, with a nutrient density score of 17.6 (DiNoia, 2014). According to the FDA, strawberries have more vitamin C than any citrus fruit, and are also rich in potassium and fiber. As an added bonus, strawberries are a good source of flavonoids (Odriozola-Serrano et al., 2008) group of phytonutrients linked to reduced risk of diabetes, heart disease, and some cancers (Arnoldi, 2004). Strawberries are about 92% water (NNDS, 2016) a proportion similar to that of watermelon; and, because of their electrolyte content, strawberries are an ideal source of hydration on warm days. If you aren’t a fan of eating a portion of plain fresh strawberries, the flavor of strawberries is delicious when sliced pieces are added to your ice water. There are also many healthy summer recipes, both sweet and savory, that contain strawberries, such as the Caprese Salad with Strawberries recipe below. Refreshing Caprese Salad with Strawberries 2 pounds fresh strawberries, stemmed and halved 2 cups bite-sized fresh mozzarella balls (Bocconcini), drained and halved 2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil 1/3 cup balsamic vinegar 3-4 fresh basil leaves, finely diced Salt, pepper to taste In medium sized bowl, toss strawberries and mozzarella balls with olive oil. Season mixture with salt and pepper. Add basil and toss again. Drizzle balsamic syrup over and around salad. Grind more pepper on top and serve. References: Di Noia J. Defining Powerhouse Fruits and Vegetables: A Nutrient Density Approach. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2014;11:E95. Odriozola-Serrano, I., Soliva-Fortuny, R., & Martín-Belloso, O. (2008). Phenolic acids, flavonoids, vitamin C and antioxidant capacity of strawberry juices processed by high-intensity pulsed electric fields or heat treatments. European Food Research and Technology, 228(2), 239-248. Arnoldi, A. (Ed.). (2004). Functional foods, cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Elsevier. National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 28 slightly revised May, 2016, Software v.2.6.1.  Summer intensives typically involve long training days. A dancer may train 6-7 hours a day for 5-6 days a week. It is important that a dancer is physically prepared to sustain these long hours to avoid overuse injuries and burnout. Preparing for Long Training Days:

Come Back Stronger Avoid working through through fatigue, illness, or injury. Always seek help from a medical practitioner if an injury occurs. Ensure that you are getting adequate rest in between training days to prevent tissue damage. The muscle requires 12-24 hours of rest following intense levels of physical activity in order to heal and repair damaged tissue prior to additional workouts (Koutedakis 2000). Set a mandatory rest period after summer intensives and avoid jumping into another intensive. It is recommended that a dancer takes a rest period of 2-5 weeks after an intensive or performance season to improve/maintain strength, flexibility, and aerobic capacity. Cross-training can be performed during rest periods (Koutedakis 2004). A rest period is critical for adequate recovery and time to reflect what you have learned. 1) Koutedakis, Y., & Jamurtas, A. (2004). The dancer as a performing athlete. Sports Medicine, 34(10), 651-661. 2)Bullock-Saxton, J. E., Janda, V., & Bullock, M. I. (1994). The influence of ankle sprain injury on muscle activation during hip extension. International journal of sports medicine, 15(06), 330-334. 3)Koutedakis, Y. (2000). " Burnout” in Dance: the physiological viewpoint.  Rest is essential for recovery and healing. It is a recommended to take a couple weeks off after a summer intensive. Adjustments in food intake should be made during these rest periods. Typically, one week is not enough time for your metabolic rate to decrease or for lean mass to dissipate significantly. However, durations longer than one week can result in loss of muscle mass and fat gain if you're not supplementing with resistance training and/or adjusting calorie intake. Plan to make small, simple changes to account for the reduced calorie expenditure when you're not dancing. Be careful not to overcompensate with extreme calorie restriction.This is counterproductive and can cause muscle loss, illness, and injury when you begin training again. What adjustments should be made to diet during the off-season?

Rather than restricting calories during vacation or off-season, consider cross-training with cardio and resistance training. Low-impact, moderate-intensity cardio such as swimming or fast walking are excellent options to allow for extra calorie burning and promote muscle retention. Walking at ~3.8 to 4 miles per hour (3 to 4 miles/day) or swimming for 30 minutes at a moderate intensity are good options. Add light resistance training with weights, Pilates, or yoga while on a break from dance in order to maintain flexibility and promote muscle gain. Enjoy your summer and remember that you deserve a break! 5/9/2018 0 Comments Dancing Through Burnout Burnout or overtraining can be characterized by:

Risks for burnout and injury:

Signs/symptoms of burnout:

Solutions and setting realistic expectations: 1) Allow for full rest days in between heavy training days. This will provide adequate time for tissue healing and recovery and prevent further tissue damage. 2) Set mandatory rest periods after performance seasons and summer intensives. It is recommended that a dancer takes a rest period of 3-5 weeks off from dance. Research shows that rest periods improve/maintain strength, flexibility, and aerobic capacity. Cross training can be performed during rest periods (Koutedakis 2004). 3) Get adequate sleep. Dancers may need up to 9 to 10 hours of sleep per night during intense training periods. Set an early bedtime for yourself and try to avoid screen time distractions before bed. 4) Eat a balanced diet. It is important to have adequate nutrition to boost your immune system and optimize your performance. 5) Don’t work through fatigue, illness, or injury. 6) When returning to dance, slowly ramp up activity load. Consider starting with a modified dance schedule when returning from rest periods. 7) Increase endurance. Most injuries occur when a dancer is fatigued and therefore it is important to improve aerobic capacity to delay fatigue. About 20 minutes of moderate to vigorous cardiovascular exercise such as swimming or cycling can bring about aerobic fitness increases. Swimming is a preferable choice for improving endurance over activities such as running or cycling, which place much more demand on the lower extremities (Koutedakis 2004). 8) Increase muscle strength. Body conditioning, weight lifting, and pilates are excellent for increasing lean muscle mass. 9) Address the signs of burnout early to avoid prolonged symptoms. 10) Consider reducing your schedule intensity if you are dancing > 5 hours a day or > 20 hours per week. REFERENCES: 1) Koutedakis, Y. (2000). " Burnout” in Dance: the physiological viewpoint. 2) Koutedakis, Y., & Jamurtas, A. (2004). The dancer as a performing athlete. Sports Medicine, 34(10), 651-661.  Dancers consume fewer calories than they expend (Dahlstrom et al., 1990; Beck et al., 2015; Hassapiduo et al., 2001; Doyle-Lucas et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2017) due to busy schedules, deliberate calorie restriction, pressure to maintain low body weight, and a lack of knowledge. Taking class on an empty stomach increases muscle breakdown, which is undesirable for dancers who need strength to dance. It is critical that dancers consume carbohydrates prior to training to reduce muscle fatigue and help preserve muscle fibers that generate power for jumping. The purpose of a pre-exercise meal - consumed within an hour or less before training - is to hydrate, top off glycogen stores, and decrease hunger. If you take a class early in the morning, you have most likely fasted overnight and will need carbohydrates to help fuel your first class. Consuming carbohydrate spares the use of protein for energy, thereby freeing up protein to synthesize muscle and repair tissue. Poor nutrition may result in the following consequences:

Recommendations Dancers should consume about 15 calories per pound body weight, plus the training energy expenditure, which is approximately 200 calories per hour of class or rehearsal. For example, a 130-pound (60-kg) dancer might need 1,860 calories per day plus an additional 500 to 800 calories to meet the demands of class, rehearsal or performance that day, for a total of 2,360 to 2,660 calories. Nutrition needs are very individualized, so it is important that dancers seek dietary advice from qualified specialists (i.e., a Registered Dietitian for dancers). References: Brown, M. A., Howatson, G., Quin, E., Redding, E., & Stevenson, E. J. (2017). Energy intake and energy expenditure of pre-professional female contemporary dancers. PLoS ONE, 12(2), e0171998. Dahlstrom M, Jansson E, Nordevang E, Kaijser L. (1990). Discrepancy between estimated energy intake and requirement in female dancers. Clinical physiology; 10(1):11-25. Epub 1990/01/01. Hassapidou MN, Manstrantoni A. (2001). Dietary intakes of elite female athletes in Greece. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics: the official journal of the British Dietetic Association;14(5):391-6. Epub 2002/03/22. Kostrzewa-Tarnowska A, Jeszka J. (2003). Energy balance and body composition factors in adolescent ballet school students. Polish Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences;12(3):71-5. Beck KL, Mitchell S, Foskett A, Conlon CA, von Hurst PR. (2015). Dietary Intake, Anthropometric Characteristics, and Iron and Vitamin D Status of Female Adolescent Ballet Dancers Living in New Zealand. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab; ;25(4):335-43. Epub 2014/11/12. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2014-0089 25386731 Doyle-Lucas AF, Akers JD, Davy BM. (2010). Energetic efficiency, menstrual irregularity, and bone mineral density in elite professional female ballet dancers. J Dance Med Sci;;14(4):146-54. Epub 2010/01/01. 21703085 Hirsch NM, Eisenmann JC, Moore SJ, Winnail SD, Stalder MA. (2003). Energy Balance and Physical Activity Patterns in University Ballet Dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science;7(3):73-9. Sousa, M., Carvalho, P., Moreira, P., Teixeira, V. (2013). Nutrition and Nutritional Issues for Dancers. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 28, 119. Montanari, A., & Zietkiewicz, E. A. (2000). Adolescent South African ballet dancers. South African journal of psychology, 30(2), 31-35. |

CategoriesAll Cross Training Injury Prevention Nutrition Recipes Wellness Archives

October 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed