|

5/26/2021 7 Comments Understanding Hypermobility What is Joint Hypermobility? Joint hypermobility refers to greater than normal range of motion in a given joint. Excessive range of motion can be attributed to factors such as bone shape, hormonal influences, impaired proprioception, reduced muscular strength, and decreased collagen strength (Knight 2012). Collagen is a structural protein within connective tissue. Fascia, ligaments, joint capsule, tendons, skin, blood vessel walls, gastrointestinal lining, and respiratory tracts contain connective tissue. Defects in connective tissue proteins contribute to joint laxity and can result in widespread symptoms (Hakim 2015). What are hypermobility disorders? Hypermobility disorders refer to a group of conditions involving symptomatic joint hypermobility. Some hypermobility disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome are caused by abnormal structure and function of collagen and connective tissue proteins. Hallmark features of connective tissue disorders include stretchy skin, loose joints, and fragile tissues (Simmonds 2007). What are common signs/symptoms of Hypermobility disorders?

Joint hypermobility is common among dancers and rhythmic gymnasts because of the flexibility demands in both disciplines. How do we screen for Hypermobility? The 5-point hypermobility questionnaire, Beighton scale, and Brighton criteria are useful screening tools for hypermobility. Two positive responses on the 5-point questionnaire provides a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 85% for detecting joint hypermobility (Kumar 2017). How is Hypermobility diagnosed? Joint hypermobility is identified through a comprehensive patient history as well as a variety of clinical tests. How can Physical Therapy help? Physical therapy can play a vital role in providing treatment strategies for individuals with joint hypermobility to improve joint stability, reduce pain, and improve function. Treatments may include:

References:

7 Comments

As dancers return to the studio, it is important to gradually introduce jumps to prevent lower leg injuries. Foot and ankle injuries are often incurred during dynamic movements like jumping, and improper flooring, poor technique, and fatigue can increase the risk of injury.

Here are some important tips to lessen the likelihood of sustaining injury during jumps:

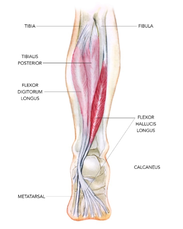

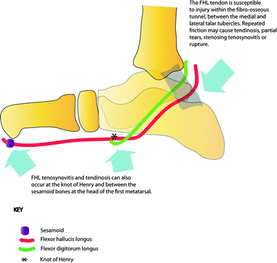

References: Russell J. A. (2013). Preventing dance injuries: current perspectives. Open access journal of sports medicine, 4, 199–210. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJSM.S36529  Do you feel pain or clicking in the back of the ankle joint and/or big toe joint with pointing the foot? Is it painful to tendu, releve, plie, or go en pointe? If so, it may be attributed to flexor hallucis longus (FHL) dysfunction. This is a common overuse injury seen in dancers and is often referred to as “dancer’s tendinitis” (Wentzell, M). The FHL plays a major role in foot/ankle stabilization and balance on pointe and demi pointe. Because the FHL muscle crosses two joints, its demands are up to three times higher than that of single joint muscles (Wentzell, M), making the joint especially susceptible to overload with repetitive pointe work, releve, and extreme ranges of plantarflexion. The FHL muscle originates on the posterior fibula. It passes under the medial malleolus through a fibroossues tunnel (green arrow on the far right of the image below), intersects with the flexor digitorum longus tendon (middle arrow), and passes between two sesamoid bones before attaching to the undersurface of the big toe (left arrow). During pointe work, the FHL tendon can be directly compressed as it passes through these points. Compression or entrapment at any of these sites can lead to pain and injury to the tendon. This can be the result of overuse or poor technique en pointe. Treatment

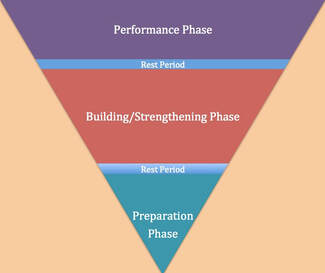

Returning to dance after an FHL injury should be gradual. Focus on mastering the basics of your technique. With early diagnosis and treatment, this can be managed to facilitate a quicker recovery and smooth return to dance. References: 1)Wentzell, M. (2018). Conservative management of a chronic recurrent flexor hallucis longus stenosing tenosynovitis in a pre-professional ballet dancer: a case report. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 62(2), 111. 2) Rowley, K. M., Jarvis, D. N., Kurihara, T., Chang, Y. J., Fietzer, A. L., & Kulig, K. (2015). Toe flexor strength, flexibility and function and flexor hallucis longus tendon morphology in dancers and non-dancers. Medical problems of performing artists, 30(3), 152-156. Photo credits: 1) https://www.sportsinjurybulletin.com/the-flexor-hallucis-longus/ 2) Chew N.S., Lee J., Davies M., Healy J. (2010) Ankle and Foot Injuries. In: Robinson P. (eds) Essential Radiology for Sports Medicine. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-5973-7_3  Photo credit: The Healthy Dancer Blog Photo credit: The Healthy Dancer Blog Dancers often ask themselves: Do I need to take time off after a performance? How long should I take for a break? How can I safely train to get in shape after a break? Is it safe to do multiple dance intensive programs? Dancers need to know that sufficient rest and recovery periods are needed to reduce the negative effects of overtraining. Lack of recovery time can adversely affect technique, energy level, mood, performance, strength, and injury risk. In addition, a gradual return back to dance is needed after a break to avoid injury and can be implemented through a periodization program. Periodization involves a gradual increase in training intensity alternating between work and rest with the dance performance at the peak of the cycle. This type of progression allows for recovery and prevents overtraining. A periodization schedule can be broken up into four phases: preparation, building, performance, and rest.

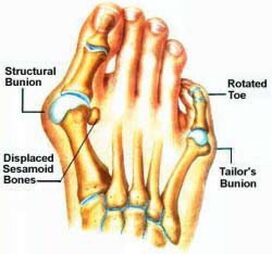

Periodization is underutilized in dance training, yet is essential for ensuring peak performance and longevity in dance. If you have been on a hiatus from your typical dance class schedule, consider using a periodization approach as you return to your regular dance training. References: Quin, Edel & Rafferty, Sonia & Tomlinson, Charlotte. (2015). Safe Dance Practice: An applied dance science perspective. 5/5/2020 4 Comments Bunion ManagementWhat is a bunion?

What are the common signs/symptoms?

What are the risk factors?

Can I prevent bunions from getting worse?

What can I do to improve my bunions?

Shiel,W.Bunions(HalluxValgus). https://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=2552. Accessed April 4, 2020. Howell,L.Does Pointe Work Cause Bunions? https://www.theballetblog.com/portfolio/does-pointe-work-cause-bunions/Updated August 31, 2010. Accessed April 4, 2020. 4/7/2020 1 Comment KEEPING IN SHAPE DURING A BREAKSET GOALS:

TIPS FOR SETTING GOALS

USE THIS TIME TO CATCH UP ON REST:

MAINTAIN ADEQUATE NUTRITION:

IMPROVE OVERALL FITNESS LEVEL

Online resources: *Health en Pointe individual nutrition and physical wellness sessions (by appointment) *Lisa Howell ballet blog training at home series: https://www.theballetblog.com/blog/training-at-home/; *Dance prehab digital for videos to improve dance foundations as well as individual wellness/dance-specific training sessions: https://danceprehab.com/login/) Inflammation is the body’s normal response to promote healing when the body is fighting infection related to injury, wounds, allergens, toxins, or infection. Typical signs of inflammation include swelling, pain, and redness. In contrast, signs of inflammation may not be apparent with chronic inflammation. Chronic inflammation is typically caused by excess body fat or immune dysfunction. While acute inflammation promotes healing, chronic inflammation can result in DNA damage and increase cancer risk.

Despite the numerous “anti-inflammatory diets” promoted online, research is barely emerging in regards to diet and inflammation. So far, scientific studies indicate that consuming a variety of nutritious foods may help reduce inflammation and keep chronic inflammation at bay. Foods that enhance immune function are also important in fighting inflammation. Here is what we know thus far about foods and inflammation:

Tips for reducing inflammation:

In addition to a healthy diet, inflammation can be reduced by getting adequate sleep, remaining physically active most days of the week, and maintaining a healthy weight.  Once a dancer is cleared to begin pointe work, they must find the most appropriate pointe shoe. Locating an experienced pointe shoe fitter is essential. Josephine Lee is the founder of ThePointeShop and is a former dancer and highly experienced pointe shoe fitter. Here are some of the tips she offers to the novice pointe student: Should pointe work hurt? Pointe work is not comfortable but it should not be so painful that you would want to quit. If it is, the dancer may need to get reassessed to look at the fit of the shoe and/or address any technical faults. Will I always stick with the same shoe type? The shoes you start with will typically be different than shoes you wear as you reach a more experienced level. Some dancers stick with the same shoes throughout their career but it is more common to see them switching shoes especially when you are starting out. How often do I need to get re-fitted? For the first couple years you are en pointe, it is recommended that a dancer gets re-fitted every time they need new shoes. Once you become a bit more experienced and are reordering shoes more frequently, you can just get reassessed every year or whenever you are experiencing issues. Why can’t I get over the box? This can be attributed to the wrong box shape, incorrect vamp length, incorrect shank hardness, foot/ankle weakness, or lack of range of motion in the foot/ankle. Why is my foot unstable en pointe? It could be due to the box being too tapered or narrow, or a shank that is too soft or hard. A tapered box results in a more narrow base of support, making it difficult to balance. A shoe that is too soft may not give enough support while a shoe that is too hard may be too difficult to control. Do stronger feet need a harder shank? Stronger feet don’t usually require a hard shank. What type/how much padding do I need? Less is more. Less padding creates better control for foot articulation and balance. The purpose of padding is to fill in the spaces of the shoe so that your foot fits the shoe better. Do soft shoes die faster? Not necessarily. Sometimes hard shoes may snap and die faster. Having poor muscle/motor control will cause a shoe to break in faster. On the other hand, if the shoes are too soft, the shank may bend under the weight easier. How do I get my pointe shoes to last? Moisture kills the shoe, so keep the shoe dry! It takes 36 hours for a pointe shoe to die and it is recommended to rotate shoes. Using jet glue and carrying the shoes in a mesh bag outside of the dance bag will help reduce excess moisture. Why does my foot sickle when I go en pointe? This could be a result of the shoe being too tapered, incorrect shank hardness, pain in the big toe, or the shoes may be the wrong width. What is the best time of day to get fitted? It depends on how the dancer’s foot responds to dancing. Some feet shrink after dancing, and others will swell. It is very individualized. 12/3/2019 1 Comment Finding the Right Pointe Shoe With a vast number of various pointe shoes and styles, finding the right balance between shoe flexibility, correct fit, and support can be challenging. The shoes must have enough movement to allow the dancer to get fully onto the toe box in order achieve full plantar flexion. They must also have adequate support to allow the dancer to put full weight through the tips of the toes without collapsing. Without adequate support, the dancer will place excess load on the muscles, ligaments, and joints of the foot/ankle. Since pointe shoes have poor shock absorption, dancers must rely on good core stability and lower body strength to reduce the impact on the foot/ankle. Poor technique, fatigue, and improper fitting pointe shoes can increase the risk for injury. For example, the vamp of the shoe must match the foot shape. If the vamp is too low, the foot spills out of the shoe and loses stability. This can increase the risk for fracture at the midfoot or second metatarsal. If the vamp is too high, the dancer won’t be able to point the foot. Improper length of a pointe shoe can result in adverse consequences for a dancer: excess length of a shoe leads to instability and a short-fitting shoe can cause compression of the toes. The vamp/platform of the shoe loses its stability when the shoes have excess wear and tear, and dancing on dead shoes can increase the risk of stress fractures, ankle sprains, metatarsal/tarsometatarsal sprains, Achilles tendinitis, Flexor Hallucis Longus tendinitis, and injuries to the knees, hips, and spine. Next month’s post will feature Josephine from The Pointe Shop. She will provide more tips on finding the right pointe shoe. References: 1) “Principles of Dance Medicine, Functional Tests to Assess Pointe Readiness.” A webinar through the Harkness Center for Dance Injuries. Accessed Feb 23, 2017. 2)Shah S. Determining a Young Dancer’s Readiness for Dancing on Pointe. Curr. Sports Med. Rep., Vol 8, No. 6, pp. 295-299, 2009. 3) “Matching the shoe to the dancer.” A webinar through the Harkness Center for Dance Injuries. Accessed Nov 20, 2019.  Resistance training is essential for facilitating muscular development and fostering strength gains in young dancers. Rapid growth periods during adolescence can lead to reduced strength, impaired balance, and decreased flexibility, which can alter technical ability and increase the risk of injury [1]. Thus, it is recommended to start strength training before puberty to reduce the risk of injury and promote strength gains. Muscular development in adolescents: Peak gains in strength typically occur one year after peak height velocity is reached. Late maturers may gain strength later and may not obtain peak strength until their 20s or30s. Differences in hormone levels account for differences in strength gains between boys and girls. Testosterone, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factors account for increased muscle bulk and accelerated strength in boys. Increased muscle mass typically proceeds strength gains [2]. Key aspects to developing a strength program: It is important to target areas of individual weakness when designing a strength program. Pelvic stabilization,, gluteal, and abdominal strengthening are keys to improving neuromuscular control of the lower extremities. A progressive resistance program can increase muscular strength/endurance in as little as 6 to 8 weeks (Stalder, M). Most programs require 2 to 3 days of resistance training per week to see strength gains. Performing high repetitions with lower weight will target muscle endurance, whereas performing fewer repetitions with higher weight will target muscle strength. It is essential to have adequate supervision by a healthcare professional during training to ensure proper progression of training loads and correct technique to avoid injury [4]. Benefits of strength training:

References 1) Delegete, A. Health Considerations for the Adolescent Dancer. A webinar through the Harkness Center for Dance Injuries. Accessed September 23, 2018. 2) Haff, Gregory G. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning 4th Edition 2016. Pages 144-145. (https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/pluginfile.php/617068/mod_resource/content/1/e217_1_excf223_nsca_chapter7_p144_145.pdf) 3) Stalder, M. A., Noble, B. J., & Wilkinson, J. G. (1990). The effects of supplemental weight training for ballet dancers. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 4(3), 95-102. 4) Stracciolini, A., Hanson, E., Kiefer, A. W., Myer, G. D., & Faigenbaum, A. D. (2016). Resistance training for pediatric female dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 20(2), 64-71. |

CategoriesAll Cross Training Injury Prevention Nutrition Recipes Wellness Archives

October 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed